Ocean wind farms: Challenges on horizon

By Michele Hallowell; guest column in May 2013 Commercial Fisheries News www.fish-news.com/cfn

The intersection of ocean wind energy development and commercial fishing is about to become very real for US fishermen.

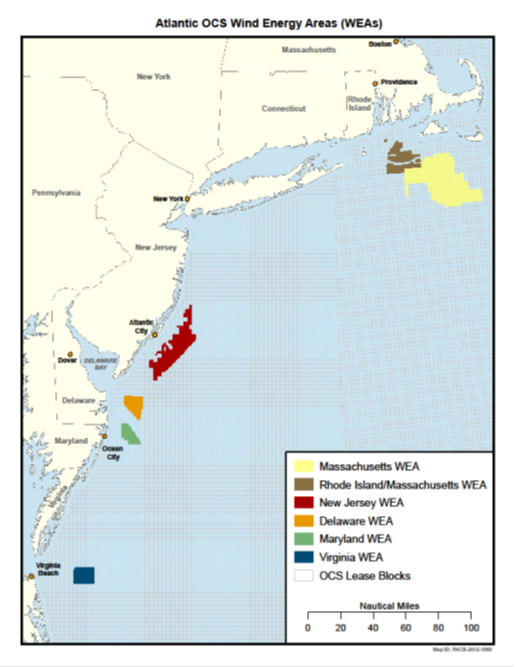

In federal waters alone, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) has created 11 wind energy areas (WEAs) along the East Coast to date and more are anticipated.

BOEM will issue leases for the outer continental shelf in these WEAs to ocean wind energy developers for up to 23 different wind farm projects. These are in addition to the five active leases BOEM already issued between 2005 and 2012, as well as other areas developers are eyeing. These numbers also do not account for wind energy development occurring in state waters.

The sheer expansiveness of ocean wind development means it will affect almost all commercial fishermen. For perspective, the Massachusetts WEA and Rhode Island/Massachusetts WEA, which neighbor one another and form a contiguous area, cover 1,591 square miles of the ocean. The entire state of Rhode Island covers only 1,214 square miles.

In mid-March, I and several other US fishing industry representatives traveled to England to learn how ocean wind energy development has affected commercial fishermen there. We also toured the Thanet Wind Farm off the southeastern England port of Ramsgate aboard a private vessel.

One lesson learned from this trip stood out among all the others: How a wind farm affects a fisherman depends on what he’s doing on board his vessel at any point in time.

If he’s simply transiting through the farm in good weather, wind turbines create few problems. The farms themselves appear like any other marine obstruction on charts. As our vessel approached the Thanet Wind Farm, the turbines were obvious to see – both out the window and on the radar – and to avoid.

Once we entered the array, however, radar was of little help. The spinning blades create an electromagnetic field that interferes with how each turbine appears on radar. Instead of showing up as points, they appear as horizontal lines that also obscure other vessels in the array, regardless of their size.

In good weather, transiting a wind farm seems not to pose a major safety risk. As one English fisherman quipped, “Just look out your window” to see what is around your boat instead of relying on radar.

But in bad weather – such as unexpected fog or a storm rolling in – the accuracy of radar is vitally important. If a fisherman cannot tell where he is in relation to fixed turbines or other vessels, the chance of an allision, the legal term for two vessels running against each other, or collision is high. And helicopter rescues cannot be conducted in most wind farms.

As more than one English fisherman said, “It makes you think twice about entering a windmill farm” for any reason at all.

Vessel Size Matters

For commercial fishermen intent on fishing inside of wind farms, the extent to which the turbine array will impact your business in large part depends on where you fish, what gear you use, and what species you target.

Vessel size matters. Smaller, nimble boats have the advantage because they have the dexterity to respond more readily to conditions in the array and they are better able to maneuver around turbines.

Larger boats, however, will have a much more difficult time responding to dangerous conditions such as swift tides, rough waves, or heavy weather. The amount of spacing between the turbines also affects how safely larger vessels can operate in the farm.

Gear type also matters a great deal.

Fishermen using rod and reel generally should be able to access fish without incident inside wind farms, provided they use sufficient caution. Recreational fishermen may even perceive the artificial reef effect of wind farms as a reason to target fish in the arrays.

In contrast, pot fishermen in the United Kingdom (UK) expressed little enthusiasm about fishing inside wind farms, despite conflicting reports that crustaceans like lobsters seemed to be more prevalent in the arrays.

Fishermen generally place pots close to where their target species are attracted. In this case, that would be at the base, or monopile, of each turbine. Doing so, however, puts gear and the vessel in harm’s way.

Strong tides and rough waters cause fixed gear to entangle easily around monopiles and underwater structures. In the UK, fishermen are advised not come within 55 meters (about 60 yards) of a turbine. Fishermen are not allowed to untangle their gear. Instead, they must report incidents of snarled gear and wait for the developer to provide replacement gear.

Even if the US does not create such “exclusion zones,” it is unlikely that fishermen will be able to safely approach wind turbines to untangle their gear.

Mobile Gear Obstacles

Developers claim that mobile gear can be used in certain wind arrays, particularly those with larger turbines. Larger turbines must be spaced farther apart to allow adequate wind to build up between them. In theory, stretched spacing creates alleys through which fishermen can tow gear.

Safely towing gear through a wind farm, however, would require a certain set of conditions. Good weather and manageable tides are a must. Fishermen and others overseas who shared their experiences indicated that strong tides and/or turbulent waters increase the likelihood that towed gear can swing away from the boat and catch on underwater structures.

It also assumes that the turbines are set in a grid pattern, yet not all wind farms have this configuration. Some arrays are set in a starburst pattern, which would be very difficult for vessels to tow gear through regardless of how far apart the turbines are spaced.

Fishermen who use bottom-tending gear, like dredges, will have the most heartache should wind farms be collocated on their fishing grounds even though, theoretically, one can dredge through a wind farm, provided the turbines are organized in grid fashion and the dredge does not cross any cables.

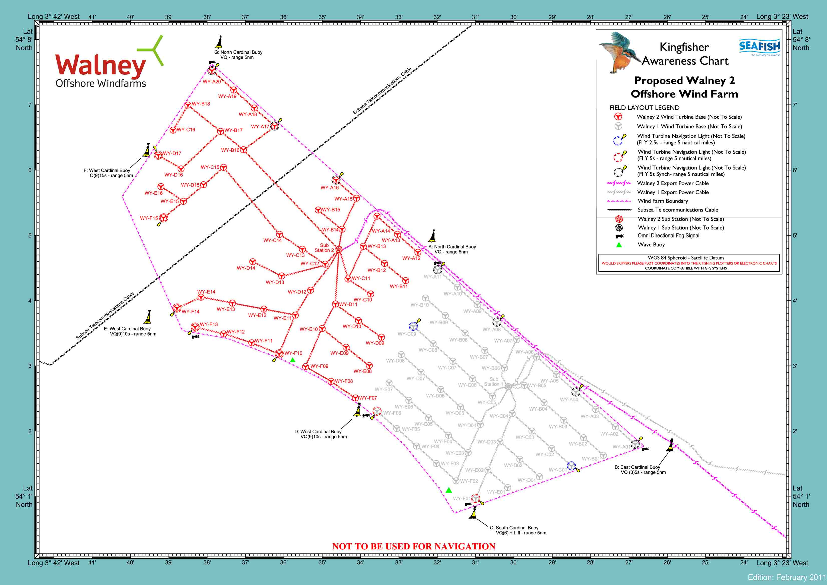

The world’s largest operating wind farm is the London Array, which has 175 turbines, 180 inter-array cables, and two export cables that bring the power ashore.

It is practically impossible for fishermen to avoid all of the cabling or rock mattressing, which is placed on the seafloor to ensure the cables do not shift, regardless of how far apart the turbines are spaced.

The difficulty associated with avoiding all of this cabling is one reason that any wind farm sited where dredging occurs will effectively exclude dredging operations, even if such operations are not legally excluded from the area.

Anyone choosing to use a dredge in a wind farm, therefore, will have to educate himself on the specific wind farm’s configuration. One will have to know where the cables are located, whether they are held down by rock mattressing, and how the turbines are spaced.

None of these facts appear on chartered maps, but this information is vital to avoid getting caught on underwater cabling. Eventually, if you want to fish offshore of Massachusetts, you will have to familiarize yourself with up to 10 different wind farm configurations to date – nine in the WEAs and the Cape Wind project in Nantucket Sound.

Author Michele Hallowell is an associate attorney in the Washington, DC office of Kelley, Drye and Warren, LLP, specializing in fishery issues nationwide, and former in-house counsel to the Maine Lobstermen’s Association.

Wind farms: Ecosystem Effects Differ Depending on Species,

Seafloor Features

By Michele Hallowell; guest column in June 2013 Commercial Fisheries News www.fish-news.com/cfn

As the siting of ocean wind energy projects continues along the East Coast, many fishermen are left wondering how wind energy development will affect fishing resources.

What is involved in testing an area for a wind farm and installing the turbine array? How will the underwater drilling, jet plowing, cable laying, and turbine installation affect fish, lobsters, and shellfish in an area? How will the resource respond once installation is complete? What will be the overall harm and benefit of a wind farm – or many of them – to target species?

Scientists and fishermen know the answers to some of these questions already. Yet some effects of wind farms are poorly understood. On a recent trip to England, fishermen there provided anecdotal evidence of what they have seen to date (see CFN May 2013 for trip background). Their experiences provide US fishermen insight on what they can expect should a wind farm be sited where they fish.

A UK wind farm under construction, chart courtesy of Tom Watson,

Fishing Industry Liaison, Irish Sea. Click on image to enlarge

Developers interested in constructing an ocean-based wind farm have to characterize the site before installation can begin. Site characterization involves conducting many surveys and tests.

Drilling into the seafloor and removing cores of sediment help developers determine the type of bottom and depth of material in a given area. Surveys of the area are conducted by towing instruments from vessels across the proposed area and by using remotely operated vehicles to roam the ocean floor and take pictures. Weather buoys and other meteorological towers also are installed.

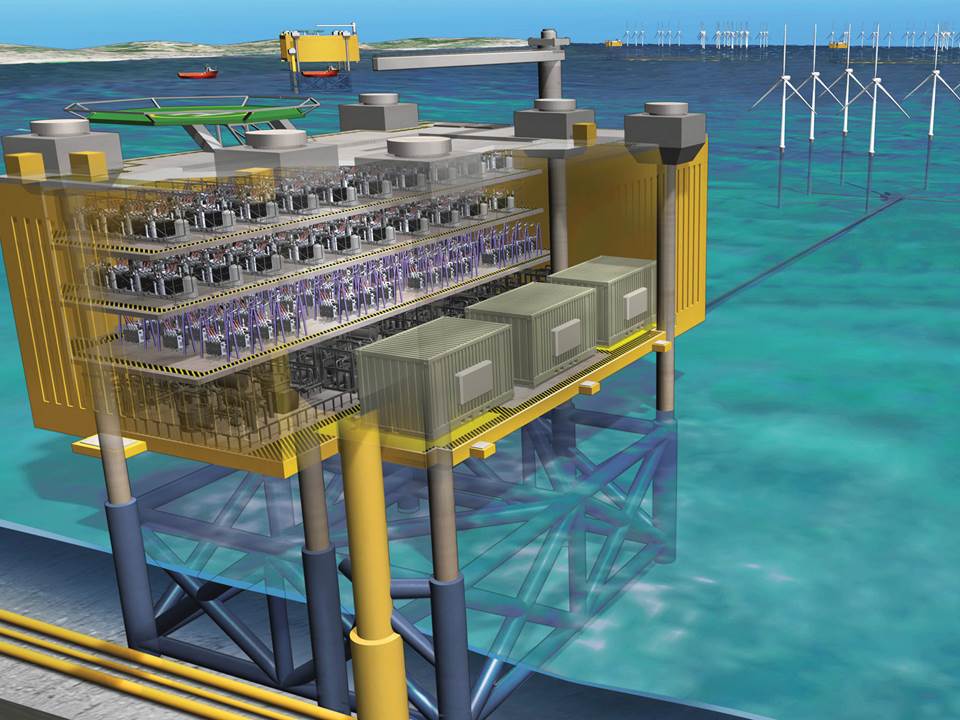

Once a site is characterized and chosen for construction, installation will begin. Cables will be laid on top of or buried under the seafloor. Burial often requires jet plowing horizontally below the seafloor. If necessary, rocks or other heavy structures may be piled on top of the cables, known as “mattressing,” to ensure they don’t move.

Wind turbines either will be drilled into the seafloor at great depths or they will sit on top of the seafloor. To reduce scour, the piles will be jacketed or have rocks piled at their base. The spinning blade will be affixed to the turbine after the base is installed.

During site characterization and construction, fishermen can expect an increase in underwater noise, vibration, and disturbance of the ocean floor. They also can expect an increase in vessel traffic and possible closure of certain areas. Testing can occur over the course of years or in spurts of condensed activity. We expect mariners notices will be issued alerting fishermen to any activity that would affect their safety or operations.

Marine Life Response

What species a fisherman targets matters a great deal in determining the extent to which a wind farm may affect his operations. The take-home message we heard from fishermen in England is that the more mobile the species, the less vulnerable it is to testing, installation, and operation of a wind farm, and the less mobile the species or resource is, the more vulnerable it is.

Some effects are temporary, while others are long lasting. Some are localized to a single turbine, while others reach far outside the wind array’s borders.

If you target mobile fish, any activity that creates underwater noise or vibrations will have the greatest impact. Fishermen can guess that mobile finfish will scatter during the most intrusive testing or installation activities, such as drilling or jet plowing. Testing and installation activities have similar impacts on mobile crustaceans like lobsters. They, too, will scatter during disruptive activities.

Once the wind farm is installed, however, some kinds of finfish are attracted to the structure. This phenomenon is not surprising because it is well known that fish often are attracted to fixed underwater structures.

Fishermen in England noted that “cod, plaice, groundfish,” and certain pelagic species tended to hide out among the turbines.

They also observed an abundance of skates in the arrays. One fisherman theorized that skates congregated in the array because the cables give off heat. Yet he also observed a reluctance by skates to cross the cables, possibly due to the electromagnetic field created by current running through the cable.

Crustaceans like lobsters and crabs, along with certain mollusks, also are attracted to the base of the turbines, especially if rock piles are used as scour protection. Mussels especially like to attach to the base and thrive in wind farms, a fact noted by fishermen and scientists alike.

Unwelcome Predators

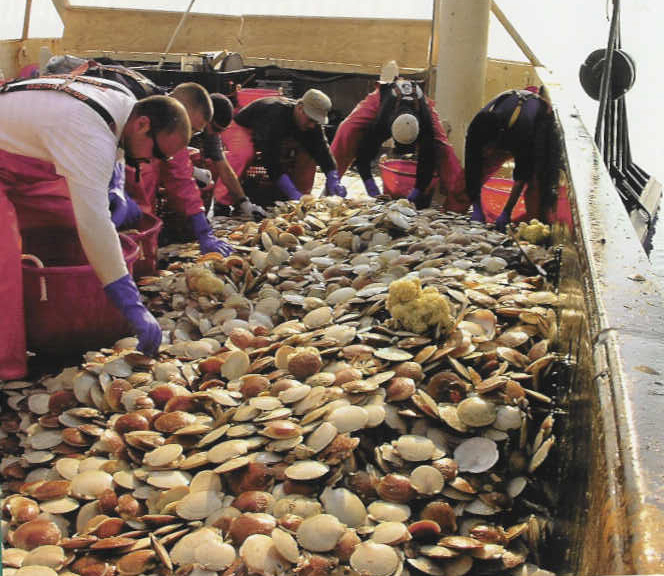

Although the artificial reef effect of a wind farm may be strong, not all species are welcome. Known predators, such as starfish, also are attracted to the arrays. Starfish prey on oysters and scallops.

For any seafloor dwelling species, such as scallops and oysters, the introduction of starfish to an area can devastate the resource. The financial hit to currently lucrative scallop and oyster beds can be extraordinary.

Another issue for mollusks and crustaceans arises if the wind farm is built in an area with sandy or muddy bottom. If the area experiences strong ocean currents or tides, sedimentation can suffocate species.

One lobsterman in England explained that years after installation, the turbines cause major scour in sandy and muddy bottoms, which causes the water to be heavy with sediment. The sediment gets in the crevices of rock structures, suffocating the lobsters that are there.

Sedimentation can be so bad that it affects fish even outside the array. We heard reports that lobsters caught in traps set in areas near arrays off of England’s south coast often are dead by the time the traps are hauled.

Oyster and scallop beds are particularly vulnerable. Drilling, jet plowing, or pile driving in these areas will crush portions of the resource. Although some species can respond to perceived danger by moving away from it, federal agencies have acknowledged that localized crushing may occur.

Furthermore, oyster and scallop beds themselves are not able to move. Stirred up sediment caused by testing and installation activities and ongoing sedimentation can blanket the beds, killing the resource. We heard reports in England that dredging in once-productive areas in and near wind farms brought up only dead fish and shellfish.

Scientists and fishermen do not know the long-term effects of wind farms on the benthic and marine environment. They don’t know how large swaths of the ocean covered in structures will affect spat settlement patterns, migratory patterns, feeding habits, or predation.

Federal agencies currently are working with limited scientific information and are basing decisions on the belief that any effects caused by wind turbines are either temporary or minimal.

For fishermen, however, these unknowns are a reminder that the ocean wind energy industry is fairly new. Any attempt to base decisions on the limited data may have unforeseen – and possibly negative – consequences.

Michele Hallowell, Rick Robins and John Williamson consult with Colin Warwick, The Crown Estate, London, GB

Lorelei Stevens photo

Author Michele Hallowell is an associate attorney in the Washington, DC office of Kelley, Drye and Warren, LLP, specializing in fishery issues nationwide, and former in-house counsel to the Maine Lobstermen’s Association.

Wind farm planning: how to be heard

By Michele Hallowell; guest column in July 2013 Commercial Fisheries News www.fish-news.com/cfn

Many fishermen are asking what they can do to preserve fishing opportunities in the wake of ocean wind energy development. The answer is threefold: be aware of what is being proposed in your area; know what governmental body is in charge; and engage early and often in the regulatory processes.

Multiple state and federal entities have authority over ocean wind energy development. In federal waters, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) has authority to lease the outer continental shelf to renewable energy developers. These include ocean wind, tidal, and wave energy developers. States have the authority to locate projects within their waters.

Projects in federal waters either are isolated or located within wind energy areas (WEAs). WEAs are best thought of as large areas zoned for wind energy development. Once created, a wind energy developer can apply to BOEM for a lease within the WEA. BOEM then expedites the review of a lease request in a WEA, and the project is fast-tracked.

Depending on developers’ interest, one or more wind farms can be sited within a WEA’s borders. For example, BOEM can issue up to five leases in the Massachusetts WEA and another four leases in the adjoining Rhode Island/Massachusetts WEA.

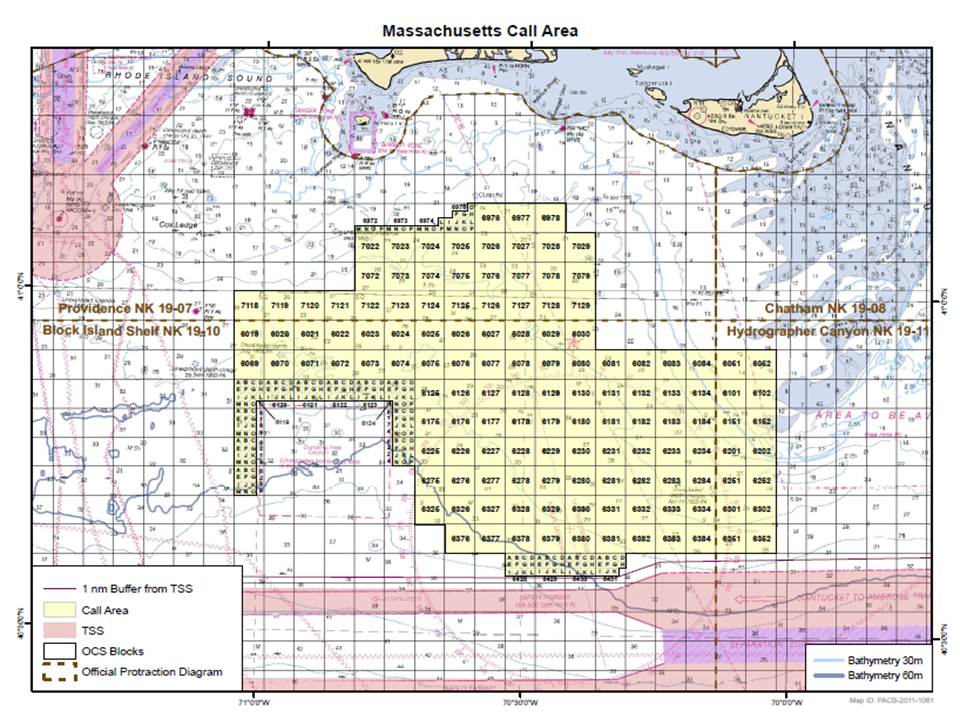

WEAs are not created in a vacuum. Instead, they are the product of state-centric intergovernmental task forces convened by BOEM. For example, the Massachusetts WEA was the product of the Massachusetts Renewable Energy Task Force, which worked with BOEM to delineate the boundaries of the WEA. BOEM then announced the proposed WEA and asked for public comment.

Several other states, including Maine, Rhode Island, New York, New Jersey, and North Carolina, have worked with BOEM to establish intergovernmental task forces.

The state-centric process creates major problems for fishermen, in large part because, for a fisherman homeported outside of a WEA state, the first time he is notified of a proposed WEA is when a notice is published in the Federal Register. So, in the case of the Massachusetts WEA, a fisherman who fishes off Massachusetts in federal waters, but is homeported outside of that state, was not given notice of the WEA – let alone a seat at the table in siting it – before it was delineated. At that point, the die was already cast.

A wind energy developer does not have to wait for a WEA to be created. It also can apply to BOEM to lease any portion of the outer continental shelf through an “unsolicited request.”

When this happens, BOEM has an obligation to first determine if there is competitive interest in the area from other developers. At the same time, BOEM must assess how the proposed project will impact other ocean users, including commercial and recreational fishermen.

The Long Island WEA grew out of an unsolicited request submitted to BOEM by the New York Power Authority.

There are opportunities to comment on an ocean wind developer’s requests for a lease in an area outside or inside a WEA when “Request for Interest” or “Call for Information” notices are published in the Federal Register.

Fishermen’s organizations should be on the lookout for these notices so that they and their members can comment on proposed projects, demonstrate where they fish with available hard data, and explain how the proposed project will affect their operations and safety. Fishing effort data, resource data, and socioeconomic data all are good things to use in support of comments.

Protecting Fishing Grounds

After these initial stages of the regulatory process, there are many additional stages involving the permitting and construction of a project that require fishermen’s input.

For example, once a WEA is created, BOEM has to take public comment on its environmental assessment and environmental impact statement for the WEA. BOEM then has to repeat that process for each individual lease proposal, taking public comment on proposed lease sales, site assessment activities, and construction and operation plans.

To date, BOEM’s initial understanding of fisheries-related issues has fallen woefully short of what is sufficient and necessary to protect commercial fishing interests.

Even though BOEM is bound by a memorandum of understanding to consult with the National Marine Fisheries Service before issuing leases, the agency has been slow to appreciate the impact wind energy projects will have if co-located on certain fishing grounds.

For example, the Massachusetts WEA originally was drawn to overlap the Nantucket Lightship Access Area, which is vitally important to scallopers. Fishermen also have not been notified in advance of a project, especially those homeported outside the state in which the project has been proposed.

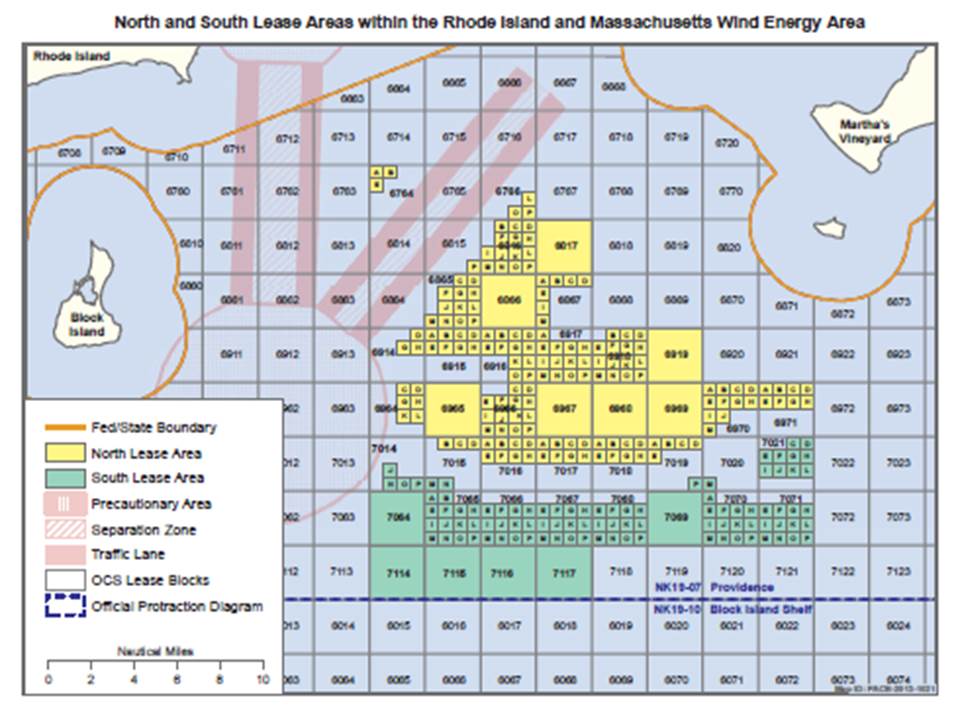

To its credit, however, BOEM did respond to fishermen’s concerns raised during the comment process by reducing the size of both the Massachusetts WEA and Rhode Island/Massachusetts WEA (see CFN June 2011).

For the Massachusetts WEA, BOEM removed the original eastern portion because it overlapped the Nantucket Lightship Access Area. For the Rhode Island/Massachusetts WEA (see chart), BOEM removed the middle bisect because fishing effort data demonstrated that more than four different fisheries operated there. Unfortunately, BOEM did not remove all of Cox’s Ledge, which any fisherman can tell you is incredibly important to multiple fisheries.

State Projects

Wind energy developments in state waters also are being sited. Some state projects are an outgrowth of state coastal and marine spatial plans. It is imperative that fishermen participate early in the development of marine spatial plans, explaining where they fish. If they don’t, regulators cannot set those areas aside to prevent wind energy development from encroaching on their grounds.

Rhode Island, for example, located its “renewable energy zones” in areas away from where most fishing operations historically occur. The state’s coastal and marine spatial planning (CMSP) process helped lessen the impact wind energy development will have on fishermen in Rhode Island state waters.

Regional Planning Bodies

Federal CMSP processes will offer similar opportunities through the work of the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic Regional Planning Bodies (RPBs). Supported by the Northeast Regional Ocean Council (NROC) and the Mid-Atlantic Regional Council on the Ocean (MARCO) respectively, these RPBs are in their infancy and are still trying to figure out their objectives.

RPB members include one regional fishery management council member and state, federal, and tribal officials. The fishing industry does not have formal representation on the RPBs, so fishermen and fishermen’s associations must engage at every opportunity to advocate for their interests.

The dizzying array of venues for ocean wind development – BOEM WEAs, unsolicited requests in federal waters, state projects, and CMSP – mean that all fishermen must stay vigilant.

Call your local representatives to get a sense of what proposals may be percolating in waters where you fish. Engage with your regional fishery management council and governor’s office to stay abreast of proposed projects. Contact your industry trade associations. Look beyond where you are homeported and pay attention to what’s happening in waters off the states where you fish. Compile useful data and make your arguments early and often. Regulators have a duty to respond to your concerns, but first, they must hear from you.

Author Michele Hallowell is an associate attorney in the Washington, DC office of Kelley, Drye and Warren, LLP and former inhouse counsel to the Maine Lobstermen’s Association.

Cable projects: Bringing wind energy to shore

By Michele Hallowell; June 2013 Commercial Fisheries News www.fish-news.com/cfn

One often-overlooked aspect of offshore wind energy development is how the energy will be brought onshore. Transmission cables carrying the energy created by offshore wind turbines must cross the ocean, make landfall – often in working waterfront areas – and connect to land-based power stations.

As much as offshore wind development may affect your operations on the water, do not overlook its onshore impacts. Major cabling project proposals are up for consideration now, making it imperative for fishermen to ensure their voices are heard.

The critical question for coastal residents and fishermen is where the transmission cable will come ashore. The most direct line from the offshore wind energy site typically dictates the result. Cape Wind, for example, plans to interconnect the power generated by the 130 turbines it wants to build on Horseshoe Shoal in Nantucket Sound at NSTAR’s West Barnstable, MA substation.

Considerations such as the area a wind farm will serve also greatly influence its transmission cable route. Deep Water Wind’s Hudson Canyon Wind Farm, which is proposed to consist of up to 200 turbines, is intended to serve western Long Island, northern New Jersey, and New York City. It will link to the three regions via a submerged transmission cable.

Transmission cables are laid either on top of or buried below the seafloor. Submerged cables are laid typically by jet plowing through the sediment and burying the cable at a depth of 6′ below the surface. The benthic community in the vicinity of these cables may suffer as a result of the installation (see Guest Column CFN June 2013 for more details).

Isolated wind farms and their accompanying transmission cables should be a major concern of coastal communities up and down the Atlantic coast. If each separate wind farm has its own transmission cable, the number of connections needed to bring the power to the grid could disrupt a significant amount of seafloor and impact working waterfront communities.

This fact in part has prompted a proposal to construct an extensive offshore “backbone” electric transmission system in the Mid-Atlantic. The project is financially backed by a group of high-profile energy and investment companies, including tech giant Google, and led by the independent transmission company Trans-Elect with Atlantic Grid Development LLC acting as project developer.

Mid-Atlantic “backbone”

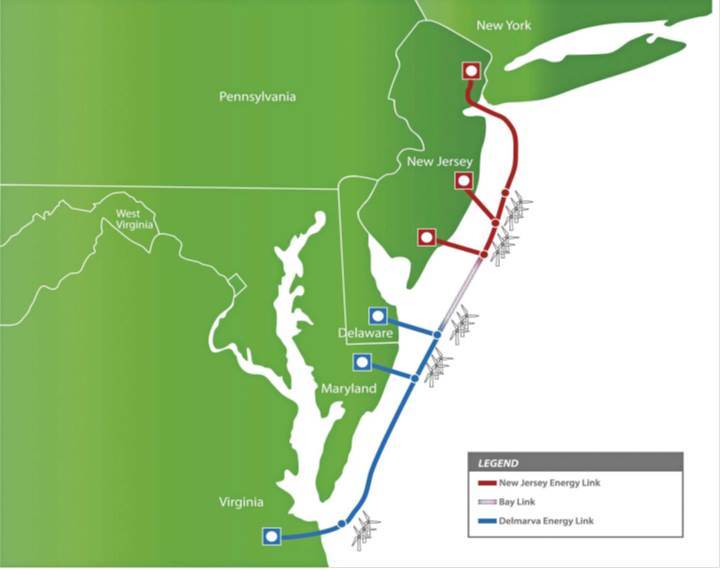

Known as the Atlantic Wind Connection (AWC), the proposed transmission project would connect wind farms off New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware, and Virginia with each other and then bring the generated power onshore in only a few areas.

As proposed, the AWC will have three geographically distinct parts and each part will be built in phases.

The New Jersey Energy Link will be built first. The initial phase of this project will connect to northern and southern New Jersey. The cables will transport energy to the electrical grid in Hudson, after traversing the Sandy Hook area, and to Cardiff near Atlantic City. The second phase adds an offshore electrical platform. The third phase adds a cable that crosses Barnegat Bay and links to the grid in Cedar.

The AWC’s Delmarva Energy Link will connect Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia. The first phase of this part of the project involves laying cables that will run ashore at Delaware’s Cape Henlopen before reaching Cape Springs and in Ocean City, MD before reaching Vienna, MD on the western side of the Eastern Shore.

These will link the Delaware Wind Energy Area (WEA) and the Maryland WEA to the shore-based power grid. The second phase connects the first phase to Virginia and adds a cable that makes landfall in the northern Virginia Beach area.

The last part of the AWC system is a connection between the system’s southern circuit, the Delmarva Energy Link, and the northern circuit, the New Jersey Energy Link. This connection across the Delaware Bay is called the Bay Link. The Bay Link will complete the continuous north-south offshore backbone.

Once constructed, the AWC will support new offshore wind energy projects in addition to those already underway. The backbone connection will remove one hurdle faced by all developers – bringing the energy to shore.

The idea is that future wind farms will be able to link to the backbone system and not have to seek separate rights of way to bring their energy onshore. For this reason, developers likely will favor building near the AWC, causing a portion of offshore energy projects to be concentrated in this region.

In addition to being heavily endorsed by supporters of renewable energy, the AWC also is seen as a boon for transporting land-based power. And, because it will be a direct conduit for “green” and “brown” energy, meaning both renewable and traditional polluting energy sources, inland public and private interest groups see it as a way of modernizing the East Coast’s power grid system.

Fishermen’s input

Despite being a massive undertaking with a lot of momentum behind it, there is room for fishermen’s input in the AWC project. The project is moving through the federal permitting process now and still is in its early stages.

AWC’s project leaders have been very active in seeking out one-on-one meetings with affected stakeholders. For those skeptical that such outreach is just a box-checking exercise, consider that Atlantic Grid Development already has responded to stakeholder concerns by moving paths of the proposed cables, reducing the length of the cabling to be laid by 255 miles, and reducing the number of outer continental shelf lease blocks that it will affect by 143.

To date the company has worked diligently “to do the right thing” by engaging directly with stakeholders instead of relying on the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management or other government agencies to lead the way.

The AWC and each wind farm proposed has the potential to affect your business if it is located where you fish. That is why it is critically important that fishermen assess the impacts these types of projects will have on their businesses and communities.

Fishermen must learn the facts and timelines of offshore wind energy projects that will affect their operations and of the cabling system that will bring the energy to shore.

These two project types may not be one in the same, but both could have major implications for working waterfronts and inshore and offshore fisheries. Most importantly, make sure you are heard in all venues available – through the planning and permitting processes and one-on-one with developers if you are afforded the chance.

Author Michele Hallowell is an associate in the Washington, DC office of Kelley, Drye and Warren, LLP, specializing in fishery issues nationwide, and former in-house counsel to the Maine Lobstermen’s Association.